Every now and again an article pops up telling us that the day is not far when humans will live on the Red Planet. This is not, the writers insist, something out of an Isaac Asimov book or the ramblings of a Star Trek fan. In my mind whether the human race is technologically close to achieving trans-planetary habitation is not the question as much as whether we should be trying to do this when we’ve been such poor stewards of planet Earth.

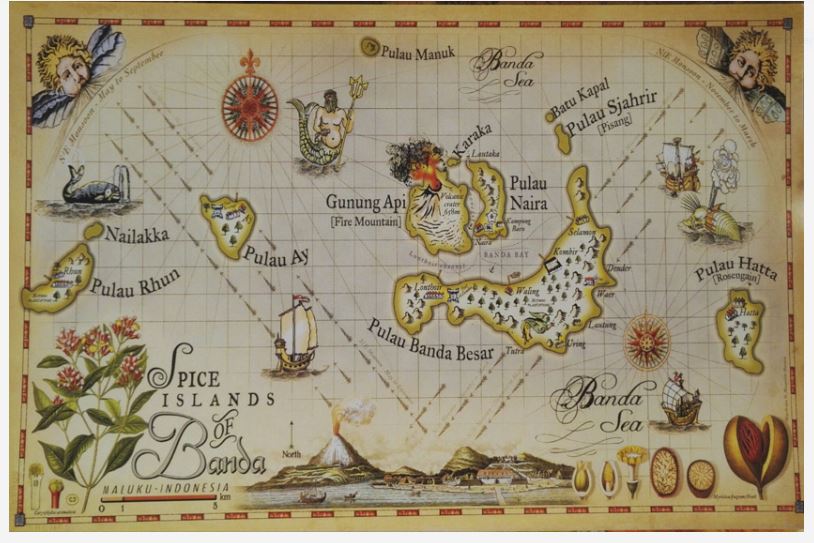

Source: Story of Nutmeg and the Banda Islands | Collin Key

This dream of colonising new planets and making them habitable is called terraforming. I learnt this from Amitav Ghosh’s The Nutmeg’s Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis. In this book, released in October 2021, Ghosh brings together his considerable storytelling skills with his interest in climate change to weave a tale that takes one from the extirpation of the Bandanese people by the Dutch in the 1600s in order to monopolise the nutmeg trade, to the Black Lives Matter and Occupy Movements at the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Nutmeg’s Curse is only incidentally about nutmegs. The nutmeg is a metaphor. To consolidate their control over the spice trade, the Dutch followed the same template as other European colonial powers - subjugate the land and the peoples and terraform the land to meet European understanding of what a productive land should look like i.e farmed monocultures. There was little interest in understanding the local ecology, peoples, customs, etc. In fact part of the approach was to dismiss indigneous knowledge, worldviews, and habits as savage, uncivilised and therefore only worthy of converting to European ideals or complete extermination. The Earth in this philosophy, which was underpinned by advances in modern scientific knowledge, especially in the biological sciences, was an inert entity created to provide endless resources for human use - a veritable cornucopia.

Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose

Ghosh makes the point that we may think we are now in the modern era where these old colonial mentalities do not hold sway. In reality they continue to buttress our interaction with each other, other species, and the planet. Climate change research, science, and technology is the domain of the West, which preaches to the rest of the world and promotes complex Big Tech fixes such as geoengineering and terraforming Mars. Humans, it is tacitly understood, are a cut above other dumb species and even among humans some are more equal than others. He contrasts this with the numerous indigenous worldviews where humans are but an inconspicuous species in the bigger plan of things, a species that does not have any more claim to the Earth than even a coronavirus. Such worldviews are dismissed by the dominant scientific narrative as quaint, romantic at best. Yet these quaint worldviews are those that respect the complexities of the natural world and promote fundamentally sustainable modes of living.

This so-called modern, scientific worldview, devoid of religion and hocus-pocus, is just a new version of the well-known trope of colonialism and racism. Reading Ghosh, brought to mind Richard Drayton’s book Nature’s Government: Science, Imperial Britain and the ‘Improvement’ of the World, that in slightly drier prose, expounds similar thoughts, looking at how exploration, ‘discovery’ of new worlds, new species that supposedly came out of Europe, was really based on indigenous knowledge which is conveniently forgotten. The Hortus Malabaricus for example, which is a 17th century treatise on the medicinal properties of the plants of the Malabar. The author credited with this work is Hendrik van Rheede. The knowledge, of course, comes from the people he interviewed - local physicians and healers.

At the same time non-white, non-European knowledge that was couched in other languages (literally and figuratively in terms of worldviews) was discounted and rubbished. This dominant view has now pervaded the globe, so much so that those of us educated in the Western scientific ethos, although we may be of the wrong colour, have also internalised the racism, the eco fascism, the colonial settler mentality. This shows in how we have treated our forests, rivers, and our indigenous communities like the Jarawas and the Onge.

This dominant narrative, Ghosh points out, has insidiously crept into the Global South where traditional divides of class and caste have strengthened and reinforced the divide between the English-educated elite who worship at the altar of modern science and the vernacular, superstitious masses. A classic example is the conservation policies followed in many countries where people are displaced to create protected areas. This model - the Yellowstone Model - is how the government in India and the urban, upper classes approach wildlife conservation, wherein if we are to preserve the many species that our country has, people must be moved out of the forests because they pose a clear and present danger to said species. These people then are encroachers, interlopers. This brought to mind a discussion several years ago in a Delhi pub. Over some chilled beer, a friend expounded on how uneducated villagers near forests must be educated about wildlife conservation. This was in response to a news article that villagers near Jorhat, Assam had killed a leopard that had entered their village. This led to a heated exchange and then a cold war as I retorted that we, sitting in the heart of built-up Delhi, whose wildlife had no doubt been destroyed by our forefathers, and sipping beer which was a non-essential item that had used up God knows how much precious resources (land to grow the barley, coal dug up in forests to power the process of making and transporting the beer, etc), had no right to judge the villagers for whom it was an immediate life or death situation.

What then? Ghosh suggests that our current path is the road to perdition and it is past time we reflect and learn from older, holistic worldviews. These, he says, hold the key to our salvation and not shifting to Mars.